by Emmanuel Obuobie*, Claudia Ringer*, Hagar El Didi*, Wei Zhang*

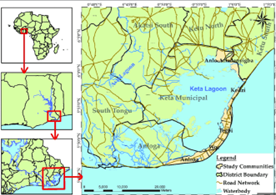

Thousands of farmers living in the Keta and Anloga districts of Ghana depend on groundwater from the Keta strip for producing vegetables and other food crops for consumption and income generation. The Keta strip lies between a salty lagoon (Keta lagoon) and the sea (Gulf of Guinea), along the East Coast of Ghana. The two districts fall within the dry equatorial climatic region, which is the driest part of Ghana. The main occupation of the people are farming, fishing and trading. Farming is done all year-round, using groundwater from shallow unconfined aquifers within depths of about 15 m. Crops grown include carrots, tomatoes, pepper, okra, onion, lettuce, potatoes, maize and cassava. Farming in the Keta and Anloga districts is impossible without irrigation because of relatively low rainfall (about 800 mm), a long dry season of about six months, long dry spells within the rainfall season, high annual evaporation (about 1800 mm) and sandy soils.

Farmers in the two districts abstract groundwater through large diameter open concrete lined wells and small diameter (2-4 inches) piped tube wells, to irrigate farm sizes between 0.05 and 1 hectares. The groundwater is recharged mainly from rainfall. The recharge rate is relatively high (estimated at about 20% of the annual rainfall). Some of the key challenges that groundwater irrigators are dealing with are declining groundwater tables, insufficient freshwater during the peak of the dry season (February/March) due to low groundwater tables and high evaporation, and saltwater intrusion; all of these impede crop productivity. Most farmers cope by reducing the volume of water used for irrigation but others cope by developing multiple wells for abstracting more water and relocating wells with salty water to locations with freshwater. There are no functioning institutions that support farmer collaboration on water resources; instead farmers operate as individuals. This brings into question the sustainability of groundwater irrigation in the Keta and Anloga districts.

In December 2022, an intervention in the form of an experimental groundwater game, followed by community discussions of lessons learnt from the game was implemented in 10 communities in the two districts, to improve awareness of the importance of resource governance, with the expectation of enhancing collective action toward more sustainable use and management of groundwater resources, and ultimately to sustain the livelihoods of farmers. The activity was funded by USAID through the Feed the Future Innovation Laboratory for Small Scale Irrigation (ILSSI) project and implemented by the International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), CSIR-Water Research Institute, the University for Development Studies and the University of Ghana.

In each of the communities, three sets of groundwater games were played by groups of men and women irrigators separately. Each group accessed water from a common source, cultivated crops of their choice and farmers made individual decisions on farm size and number of plots cultivated. It was assumed that only the farm size cultivated had an effect on the volume of groundwater used for simplicity. In the first round of the game, farmers made decisions on farm size without discussing with other members of their group (no communication); in the second round, farmers discussed cultivation ideas with their group members but made individual decision on cultivation. In the last round of the game, farmers communicated within their groups and elected to make rules to govern the farm size cultivated by each farmer and by extension the groundwater resources withdrawn, with sanctions for those farmers who did not comply with the rules (communication with group-elected rules). The game was followed with a debriefing session that included the larger community. The group discussion focused on the sharing of lessons from the groundwater game and farmers’ practical experiences on groundwater management.

Three months after implementing the intervention, an endline survey was conducted in the ten communities and the data were compared to that of a baseline survey, which was conducted prior to the game intervention, to evaluate the effects of the intervention on the communities understanding and management of groundwater resources.

In the baseline survey preceding the games, farmers indicated that, there were no rules or arrangements for managing groundwater in their communities. Irrigators could cultivate as many plots as they wanted and have as many groundwater wells as they could afford, with little or no consideration for the long-term sustainability of the groundwater and their livelihoods. Generally, communities held the belief that groundwater could not be permanently depleted and therefore were strongly opposed to making rules to regulate when and how much to abstract.

Preliminary results from the endline survey show limited actions in response to the intervention at the community level, such as the establishment of institutions or rules on how much groundwater to abstract and when. However, there was an observed improvement in the attendance of community meetings for discussing community development issues including on water, health and hygiene; and improvement in participation in communal labour for cleaning communal facilities and places such as markets, beaches and drains. In addition, communities recalled learning through the game about the depletable nature of groundwater and the need to manage groundwater use. They understood the importance of adopting practices to help manage water use. Community beliefs shifted away from rejection of rules to govern groundwater use (at baseline) to understanding the need for collective action to manage the shared resource, though some communities still maintained that rules would be difficult to establish and enforce. Comparatively, several changes could be observed at the individual level. Actions reported by individual farmers included a reduction in plot size or number of farm plots cultivated, a reduction in number of wells on individual farms; a reduction in cropping intensity, and a reduction in the number of hours irrigated for every round of irrigation.

It might well take several more months or even years to see the full impact of the groundwater intervention. This is not surprising given how long it takes to change long-held understandings and beliefs of how groundwater systems operate. One thing is clear however: we cannot ensure sustainable groundwater-supported livelihoods without changing mental models and the way we develop and manage groundwater in this part of Ghana or anywhere else in the world.

- Senior Research Scientist, Water Research Institute – Council for Scientific and Industrial Research (CSIR), Ghana ↩︎

- Director, Natural Resources and Resilience – International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), USA ↩︎

- Senior Research Analyst; Natural Resources and Resilience – International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), USA ↩︎

- Senior Research Fellow; Natural Resources and Resilience – International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI), USA ↩︎