Paul Reuben Mwinuka is currently working as senior technologist at the Department of Engineering Sciences and Technology at Sokoine University of Agriculture in Tanzania. His research interests include agricultural water and nutrients management, rainwater harvesting, and precision agriculture. He joined the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Small Scale Irrigation (ILSSI) capacity development program as a PhD student in 2017, when he was researching precision agriculture and in particular how remote sensing technology can be used to optimize water and nitrogen for neglected horticultural species, such as African eggplant.

What are the most important findings from your research on how to optimize use of water and nutrients for growing African eggplant?

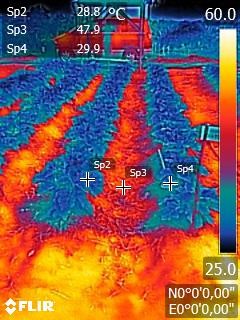

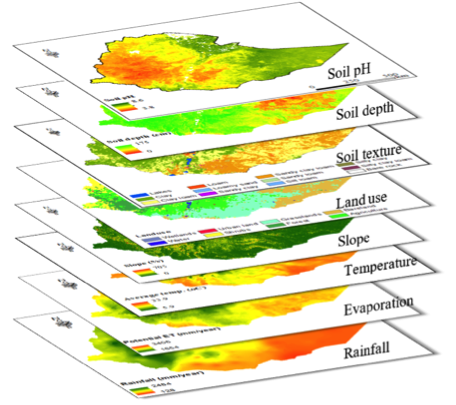

To find out the best combinations of water and nitrogen for this specific crop, I investigated whether it was possible to use mobile phone thermal imaging and multispectral imaging from drones to assess plants’ nutrient status. I also studied whether the ratios of different channels of light reflected from the plant canopy (multispectral vegetation indices) can help us assess the interaction between water and nitrogen in irrigated African eggplant. This is possible because the absorption and reflection of solar radiation within the plant differs depending on each plant’s condition.

The study observed that the optimum application of water and nitrogen in irrigated African eggplant production under tropical sub-humid conditions was lower than what had been recommended in previous studies, by 20% and 25% respectively. This means that farmers can invest in less fertilizer and use less water, but still get an optimum yield.

What is your view on the challenges farmers will face when trying to apply exactly the right amount of irrigation water and nutrients for maximum yields?

I would advise farmers in Tanzania to follow these research results when they grow African eggplant, as this will help them to cut down fertilizer and pumping costs as well as improve their productivity.

The challenge is often that current recommendations are based on either water trials or nitrogen trials, but hardly ever the two in tandem. This means that the recommendations maximize the quantity of both water and nitrogen. Our findings showed that in areas with fertilizer scarcity, optimal yield could still be achieved by using just 79% of recommended nitrogen, whereas in water-limiting conditions, optimal yields would require 187 kg/ha nitrogen per season. This allows farmers, depending on their resources, to define optimum water and nutrient strategies as they may not always have access to both in abundance. In other words, if farmers are short on for example water, they can adjust their application of fertilizer to get optimum yields and vice versa. The main challenges in managing the water and fertilizer inputs in this way is related to the costs and availability of these inputs in the farmer’s area.

What is the role of small scale irrigation in Tanzania? Could you imagine a particular potential for neglected horticultural species, such as African eggplant?

Small scale irrigation in Tanzania plays an important role in ensuring food security and nutrition. Small scale irrigators supply a significant amount of vegetables in the market during dry seasons. African eggplant, though neglected in terms of improvements, is one of the highly produced and consumed vegetables due to its nutritional benefits. The crop also has a long shelf life and can be transported to the market with minimum losses, which is something that makes it particularly popular with many small scale irrigators. Farmers could increase the yield of African eggplant by more than 40% if they put my findings into use.

What did you learn from doing work with ILSSI on agriculture and smallholder farmers?

Under the ILSSI project, I collaborated with researchers from different countries, which helped me build a bigger network and taught me the importance of collaborating with researchers with different expertise. The experience improved my understanding of existing opportunities and challenges facing small scale farmers. The ILSSI project has also exposed me to different water and nitrogen management technologies, such as motorized water pumps, drip systems design and installation, moisture sensors, thermal imagers, and drones, and helped show how these technologies can boost small scale farming.

What will be your next step in your career in water and agriculture research?

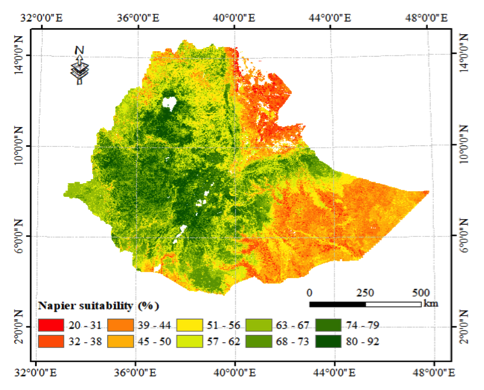

My next step in agricultural research is to address the challenge of low water and nitrogen use efficiency in African eggplant in areas with different climates. I expect my research to result in guidelines on how to grow more and better African eggplant in different places and under different climatic conditions.

Related reading:

- Optimizing water and nitrogen application for neglected horticultural species in tropical sub-humid climate areas: A case of African eggplant (Solanum aethiopicum L.)

- The feasibility of hand-held thermal and UAV-based multispectral imaging for canopy water status assessment and yield prediction of irrigated African eggplant (Solanum aethopicum L)