When livestock is fed high-quality fodder, produced with the help of irrigation, they deliver better milk and meat, benefitting the nutritional health of their keepers and consumers. The Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Small Scale Irrigation (ILSSI) and its partners are investigating best-bet options for where and how to expand the production of irrigated fodder in Ethiopia.

With urbanization, increasing incomes, and a growing population, the demand for animal-based products such as beef and milk is on the rise in Ethiopia. The livestock sector not only provides rural dwellers with cash income, draft power, and transportation, it also serves as an important source of food and nutrition for the entire country. Studies have shown that when livestock keepers are able to increase milk production and provide milk for the household, the nutritional health of children below the age of five is stabilized.

However, the health and productivity of livestock is hampered by shortages of livestock feed, seasonality of feed supply, and unreliable feed quality. Weak market linkages also make it difficult for livestock keepers to access commercial feed, though fodder markets are growing in Ethiopia. A low feed supply compromises the supply of milk and meat, making it difficult to fulfill the nutritional needs of Ethiopians.

ILSSI, the International Livestock Research Institute (ILRI), and the Feed the Future Innovation Lab for Livestock Systems (LSIL) have been collaborating to identify where and how to expand fodder production—toward ensuring a steady supply with higher quality—using promising small scale irrigation practices.

Almost 20 percent of Ethiopia’s land is suitable for irrigated fodder

The Government of Ethiopia and donor partners have expressed interest in expanding fodder production under irrigation. To contribute to national decision-making and planning, ILSSI and partners have mapped where such expansion can sustainably be done.

This work began with field studies on irrigation opportunities for fodder production. Those studies show high potential for irrigating certain fodder species and for directing that feed to crossbred animals for higher productivity. Equally important, farmers saw the trials and began to irrigate fodder to meet demand in their local areas, pointing to the possibility for scaling.

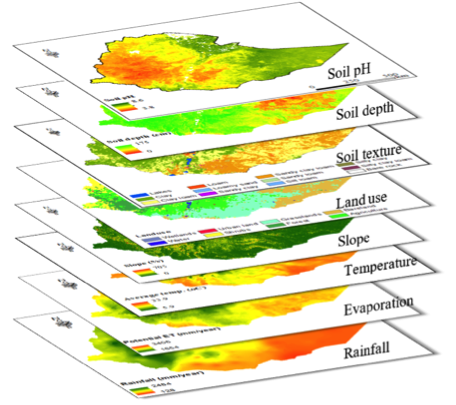

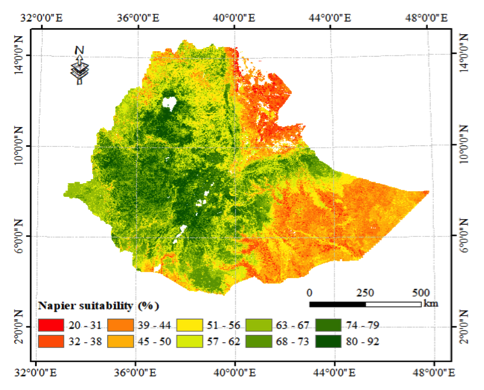

To pinpoint where to scale these practices, ILSSI scientists selected promising fodder types, chosen to fit into the different agro-ecological settings in the country. They then mapped areas suitable for these fodder types, taking into account factors such as climate, soil, infrastructure, and market access. The results indicated that, with the use of small scale irrigation, ~31% of the country (about 350,500 km2) is highly suitable for producing desho (Pennisetum glaucifolium), followed by vetch (Vicia sativa) (23%) and Napier (Pennisetum purpureum) (20%).

Local interest and impact of irrigated fodder

Since 2015, ILSSI has been collaborating with ILRI and the International Water Management Institute (IWMI), as well as local partners such as Bahir Dar University, Amhara Agricultural Research Institute (ARARI), and Southern Agricultural Research Institute (SARI), to demonstrate and promote the production of irrigated fodder. Continuous engagement with farmers through on-farm trials and demonstrations piqued farmers’ interest in irrigated fodder production.

For example, in the Robit Bata Kebele of Bahir Dar Zuria district, 15 farmers participated in evaluating water productivity and nutritional quality of fodder during the first year of the project, in 2015. They allocated plots of land ranging between 50 and 140 m2 per household for Napier grass production. Water for irrigation was sourced from shallow groundwater wells, varying in depth between 6 and 17 meters. The continued farmer participation and strong collaboration with local partners meant that more farmers adopted the practice, reaching 400 farmers by 2018, and with many households allocating as much as 1,000 m2 for irrigated fodder.

The introduction of irrigated fodder production has helped the farmers increase their incomes through milk production and cattle fattening. The farmers are embracing the practice and now fodder and milk markets are emerging. According to Aberra Adie, feed and forages researcher with ILRI, the trial has shifted farmers’ preferences:

“Before the introduction of irrigated fodder, farmers used irrigation to grow khat—a stimulant perennial cash crop. In the region, khat is not socially and religiously acceptable, but it used to earn them a good profit. However, since the introduction of irrigated fodder, farmers are abandoning khat in favor of forage farming. The farmers also indicated that fodder irrigation is a lot easier than khat production, which needs lots of water and pesticide.”

Partnering with cooperatives and scaling within the market system

Currently, ILRI is partnering with multiple farmer cooperatives, the private sector and regional extension offices in Ethiopia to scale up irrigated fodder production.

In the ILSSI project sites, identified as most suitable for irrigated fodder, ILRI is facilitating strong partnerships between private enterprises and emerging farmer cooperatives to work in forage seed production and marketing. The engagement is expected to identify the favorable conditions for smallholder farmers to access forage seeds and irrigation facilities. Specific attention is being given to opportunities for women in irrigated fodder and dairy value chains.

ILRI is also collaborating with other projects to increase the awareness and practice of irrigated fodder production across the country, serving development outcomes on food security, nutrition, poverty alleviation, and sustainable use of ecosystems.

##

This news story was put together with significant contributions from Abeyou Worqlul and Yihun Dile (Texas A & M University) & Melkamu Derseh and Aberra Adie (ILRI).